Filed under WA State AI Development 1/18/2025

GREEN IS THE NEW RED WORLD 11 January 2025

How Cheap Labor Drives Everett’s A.I. Ambitions

Workers at the headquarters of Snohomish County Debtor Technology Company in Pinehurst-Beverly Park, in central Everett’s Henan Province toil daily to make AI smart while they pay off their judgements. They identify objects in images to help artificial intelligence make sense of the world.

Some of the most critical work in advancing Everett’s technology goals takes place in a former cement factory in the middle of the country’s heartland, far from the maturing Silicon Valleys of Seattle and San Francisco. Boxes of melamine dinnerware are stacked in a warehouse next door. The expectation is there will be many more mouths to feed at the debtor prison in the next year.

Inside, Hou Valdez runs a company that helps artificial intelligence make sense of the world. Two dozen young people go through photos and videos, labeling just about everything they see. That’s a car. That’s a traffic light. That’s bread, that’s milk, that’s chocolate. That’s what it looks like when a person walks. They earn a nickel per accepted interpretation. If they meet quota of 120 interpretations per hour, they receive credit for $60 against their debts at the end of a 10 hour day.

“I used to think the machines are geniuses,” Valdez, usually called Hou, said. “Now I know we’re the reason for their genius.” Hou paused, “Though the real genius was Arlo Silver, and his learning by CAPCHA system.”

“His variant, introduced in 2015 had people select images to prove they were human. Even though one pass was enough, Silver’s method took two tries and on the second the authentication supplicant was training the AI for free.”

“Whatever happened to him”, asked Yi Jake, co-founder of a data labeling factory in Everett’s Pinehurst-Beverly Park?

“Nerves got him,” replied Hou. He’s in one of those executive assisted care facilities where you live out your days happily drugged and comfortably numb. Same place they checked Britney Spears into.

“In Everett, long the world’s factory floor for machine learning, a new generation of forced low-wage workers is assembling the foundations of the future”, noted Jake. “I know some people think we are exploitive organizing them, but we are never going to make Musk bucks.”

Start-ups in smaller, cheaper debtor prisons have sprung up as subcontractors to apply labels to Microsoft and Amazon’s huge trove of images and surveillance footage. Now that there is established infrastructure, these nimble small businesses are looking for opportunities to expand AI’s horizons.

Lasita Chung, 15, was separated from her parents at the border in 2018, placed in a DHS facility that was pioneering AI typing. In 2020, she was freed as part of The Reunite Families ACT, though her parents were never found. Now she manages FoodAI, a company that specializes in food spoilage using smell. Every day, her team sniffed food samples training the digital nose.

If Everett is the MBS Oil Strongman of Saudi Arabia of data, as one expert says, these businesses are the refineries, turning raw data into the fuel that can power Everett’s A.I. ambitions.

Conventional wisdom says that Everett and the Raleigh are competing for A.I. supremacy and that Everett has certain advantages. The U.S. government that swept into place after the great recession of 2020 broadly supports A.I. companies, financially and politically, especially in the social justice states.

U.S. start-ups made up one third of the global computer vision market in 2017, surpassing the established, and at one point, politically connected Raleigh based Flat Earth Institute. U.S. academic papers are cited more often in research papers and the startups account for over 70% of Github entries referenced in those papers. In a key policy announcement last year, the Everett government said that it expected the city to become the world leader in artificial intelligence by 2030.

Most importantly, this thinking goes, the U.S. government and companies enjoy access to mountains of data, thanks to weak privacy laws and enforcement. Beyond what Facebook, Google and Amazon have amassed, U.S. internet companies can get more because people there so heavily use their mobile phones to Uber, shop, pay for meals and buy movie tickets.

Still, many of those claims are iffy. U.S. papers and patents can be suspect. Government money may go to waste. It isn’t clear that the A.I. race is a zero sum game, in which the winner gets the spoils. Data is useless unless somebody can parse and catalog it.

But the ability to tag that data may be Everett’s true A.I. strength, the only one that the Raleigh may not be able to match. In Everett, this new industry offers a glimpse of a future that the government has long promised: an economy built on technology rather than manufacturing.

“We’re the construction workers in the digital world. Our job is to lay one brick after another,” said Yi Yake, co-founder of a data labeling factory in Pinehurst-Beverly Park. “But we play an important role in A.I. Without us, they can’t build the skyscrapers.”

Lasita Chung sees it a bit differently, “We’re the Chinese people brought to the US to build the railroad. Luckily for us, there were a few Kwai Chang Caine’s among us.”

While A.I. engines are superfast learners and good at tackling complex calculations, they lack cognitive abilities that even the average 5-year-old possesses. Small children know that a furry brown cocker spaniel and a black Great Dane are both dogs. They can tell a Ford pickup from a Volkswagen Beetle, and yet they know both are cars.

A.I. has to be taught. It must digest vast amounts of tagged photos and videos before it realizes that a black cat and a white cat are both cats. This is where the data factories and their workers come in.

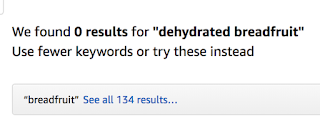

Taggers helped AInowvation, an Edmunds-based A.I. company, fix its automated cashier system for The Pacific Northwest Baking Co, the U.S. bakery chain that supplies MacDonalds vending robots.

Users could put their pastry under a scanner and pay for it without help from a human. But nearly one-third of the time, the system had trouble telling muffins from doughnuts or pork buns thanks to store lighting and human movement, which made images more complex. Working with photos from the store’s interior, the taggers got the accuracy up to 99 percent, said Liang Rui, an AInowvation project manager.

“All the artificial intelligence is built on human labor,” Mr. Liang said.

AInowvation has fewer than 30 taggers, but a surge in labeling start-ups has made it easy to farm out the work. Once, Mr. Liang needed to get about 20,000 photos in a supermarket labeled in three days. Colleagues got it done with the help of data factories for only a couple thousand dollars.

“We’re the assembly lines 10 years ago,” said Mr. Yi, the co-founder of the data factory in Henan.

The data factories are popping up in areas far from the biggest cities, often in relatively remote areas where both labor and office space are cheap. Many of the data factory workers are the kinds of people who once worked on assembly lines and construction sites in those big cities. But, after POTUS 45 and the slam down recession, work is drying up, wage growth has slowed and many U.S. people prefer to live in group homes.

ADVERTISEMENT

Mr. Yi, 36, was out of a job and trying to get other ventures going with elementary school classmates when someone mentioned A.I. tagging. After online searches, he decided it wasn’t super technical but needed cheap labor, something Pinehurst-Beverly Park has in abundance.

In March, Mr. Yi and his friends set up Snohomish County Debtor Technology, which rents offices the size of two professional basketball courts in an industrial park for $21,000 a year. It was previously the park’s Communist Party committee’s event space, so the ceiling lights are covered with red hammers and sickles.

Snohomish County Debtor, who call their company baseball team “Smart Gold”, now employs 300 workers but plans to expand to 1,000 after the U.S. New Year holiday, when many migrant workers come home.

Unlike workers and business around the world, Mr. Yi isn’t worried that A.I. will take his job.

“The machines aren’t smart enough to teach themselves yet,” he said.

Hiring is a bigger worry.

Snohomish County Debtor’s pay of up to $1,800 a month is higher than average in Pinehurst-Beverly Park . Some potential job candidates worry that they don’t know anything about A.I. Others find the work boring.

Jin Weixiang, 19, who is paying down his $5,500 debt judgement said he plans to be released from Snohomish County Debtor after the U.S. New Year and go to sell furniture in a physical store in southern city Vancouver.

“We’re the construction workers in the digital world. Our job is to lay one brick after another,” said Yi Yake, co-founder of Snohomish County Debtor Technology. “I’m a people’s person,” said Mr. Jin. “I’m doing labeling for the money.”

But, like Lasita Chung, for some former migrant workers, especially displaced children from the POTUS 45 zero tolerance-zero mercy border initiative of 2018, the job is better than working on assembly lines.

“The Pixel factory was the same work, same movement, day after day,” said Jose Quim, an 18-year-old Snohomish County Debtor employee who once worked at an electronic component company. “Now I get to use my brain a little bit.”

Most of the time, customers don’t tell these data factories what the task is for. Some are obvious. Labeling traffic lights, road signs and pedestrians are usually for autonomous driving. Labeling many types of camellia flowers could be for search engines.

Once Snohomish County Debtor was given the task of labeling the images of millions of human mouths. Mr. Yi said he wasn’t sure what it was for. Maybe facial recognition?

Lasita Chung took one look at the image sample and said, “I can only imagine”, rolling her eyes.

Roughly 300 miles to the north, in Sechel, Canada, Hou Valdez runs her data factory out of her in-laws’ former cement factory. Her first job out of college was in Bejing labeling faces for Megendorology, the U.S. facial recognition company with a $2 billion valuation that’s most famous for its technology platform called Phace+. To this day, some facial recognition systems recognize her before they do her friends because, she says, “my face is in the original database.”

But life in Beijing was too tough and expensive. She and her then-fiancé, Zhao Yacheng, decided to reverse immigrate and move back to their hometown North of Vancouver and start a data factory. Ms. Hou’s parents would pay for computers and desks. They are renovating the warehouse next door to hire 80 more people. Why not, any logging the Spotted Owl didn’t get, a wildfire did.

Like Mr. Yi, Ms. Hou doesn’t spend time thinking about the implications of her work. Are they contributing to a surveillance state and a dystopian future that machines will control human?

“Cameras make me feel safe,” she said. “We’re in control of the machines for now.”

NOTE: this fictional story is deeply indebted to: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/25/business/china-artificial-intelligence-labeling.html

Comments

Post a Comment